Mobile Malware Com.watermother25

Introduction

Hello, I’m Dızmana. Today, we will be dissecting a sophisticated piece of mobile malware. The investigation began when a friend received a suspicious SMS in Turkish: “Hello, is this photo yours?” followed by a malicious link. What made this striking was that the message originated from a known contact, indicating a worm-like spreading mechanism. I asked my friend to forward the message, and thus, the analysis began.

Malware Profile & IOCs

Before diving into the reverse engineering steps, here is a technical summary of the threat intelligence gathered during this investigation.

Malware Overview

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Malware Family | Cerberus / Alien (Banking Trojan) |

| App Name | System Update |

| Package Name | com.watermother25 |

| Dropper Pacage Name | com.android.uz032wyx |

| MD5 | E6B50F6101653E23890FB5DCCFB78D25 |

| SHA-1 | B15101F896B04C89BF4510FA344890630B7CF058 |

Command & Control (C2)

| Type | Value |

|---|---|

| Main C2 IP | 45.86.86.128 (Bulletproof Hosting) |

| Backup C2 IP | 196.251.100.103 |

Cryptography & Obfuscation

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

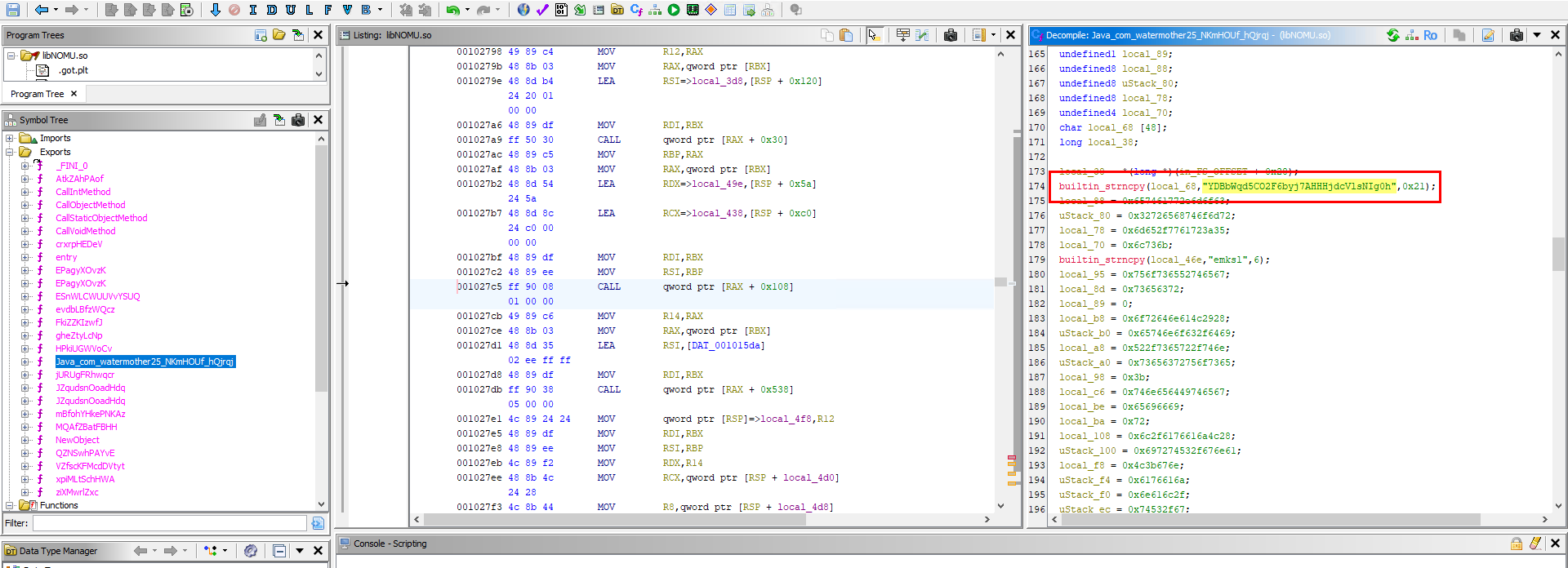

| RC4 Key | YDBbWqd5CO2F6byj7AHHHjdcVlsNIg0h |

| Usage | String obfuscation |

| AES Seed / Bot ID | 630210705 |

| Usage | Network encryption key derivation |

Targeting

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Primary Target Region | Turkey |

| Secondary Target Region | Global |

Phase 1: The Dropper

As is common with such campaigns, attempting to download the malware via a standard desktop browser failed. The C2 server was enforcing a User-Agent check to restrict access to mobile devices only. Bypassing this simple precaution was trivial; by spoofing a mobile User-Agent, I successfully acquired the sample.

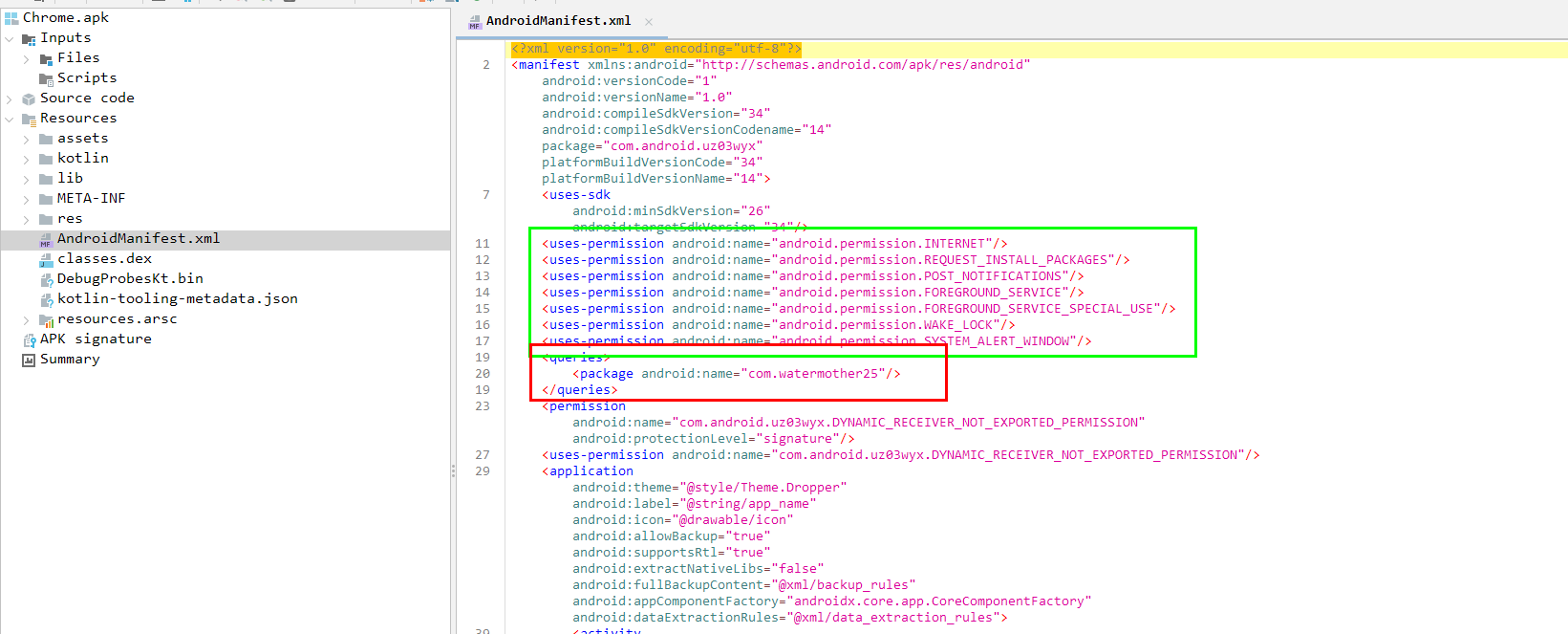

I began with static analysis, loading the APK into Jadx to inspect the source code.

The first red flag in the manifest was the excessive and suspicious permissions. While the app lacked the ability to send SMS directly (contradicting the initial infection vector), one permission stood out immediately: REQUEST_INSTALL_PACKAGES. This confirmed my suspicion: we were dealing with a Dropper.

Digging deeper into the code, I found a logic block that checked for the presence of a specific package: com.watermother25. This revealed the name of the actual payload the dropper intended to install.

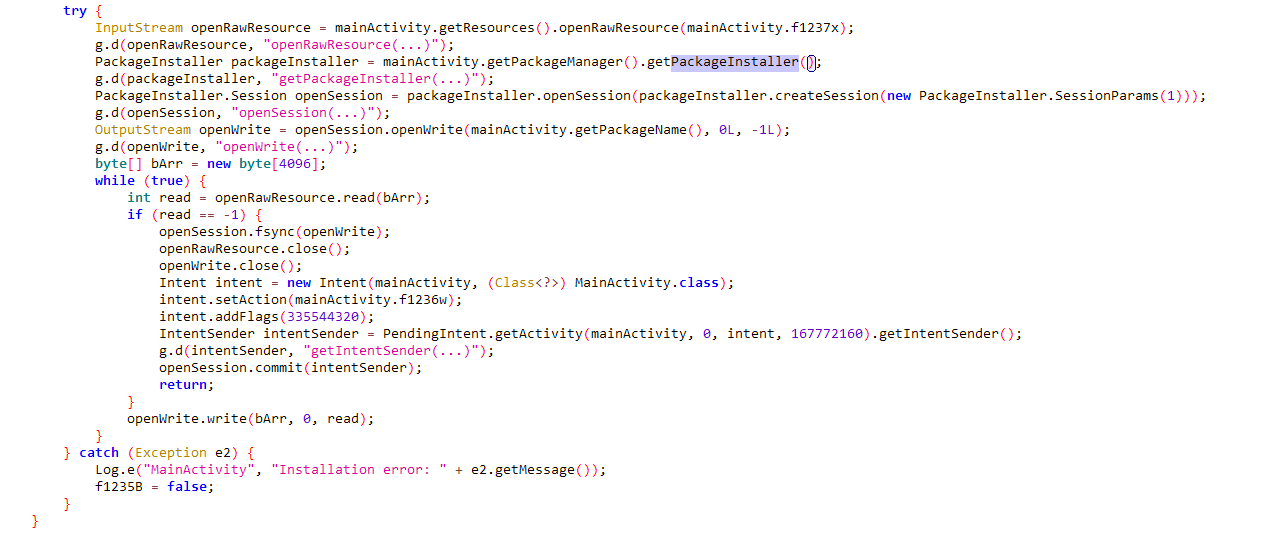

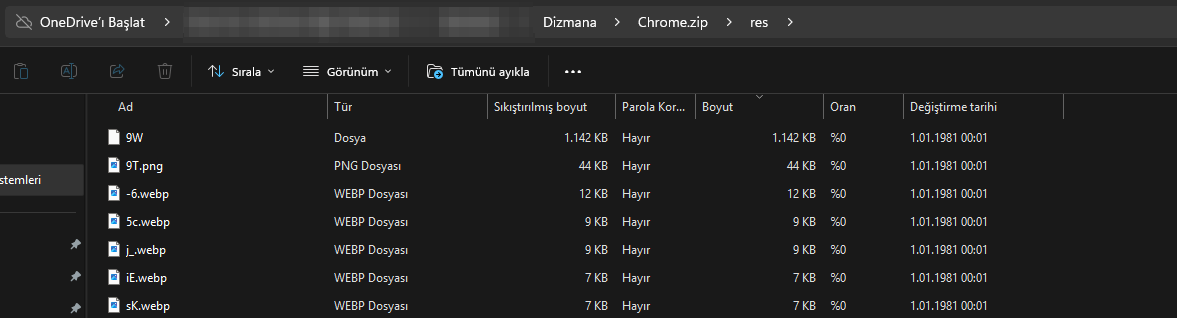

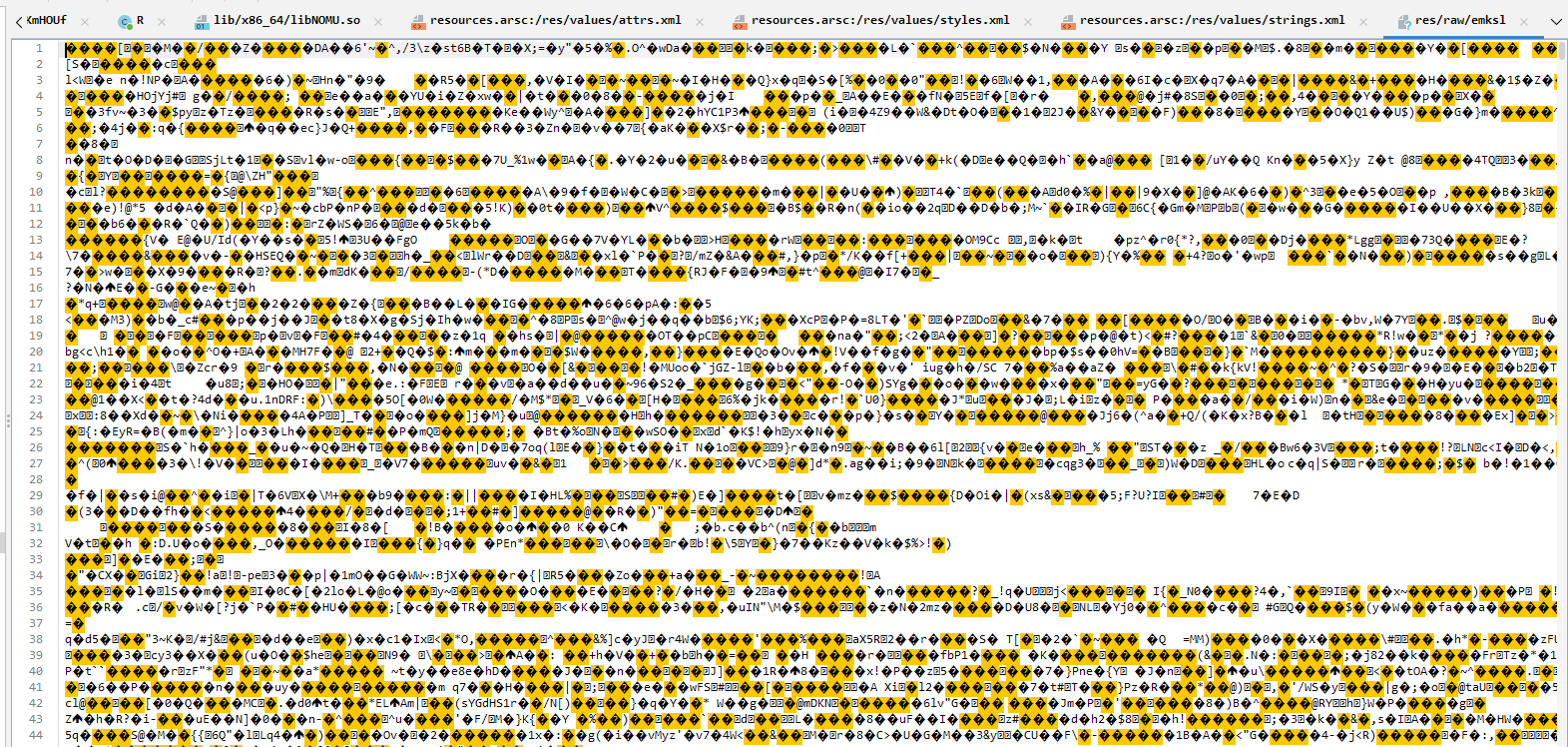

Further analysis of the MainActivity pointed towards a resource file. I decompiled the APK using apktool and sorted the files in the res/raw directory by size. There it was, staring right at me: a file named 9W. It was significantly larger than the others (approx. 1.1 MB). I extracted this file, but as I soon realized, reading this malware’s code wouldn’t be as easy as finding it.

Phase2: Analyzing the Payload

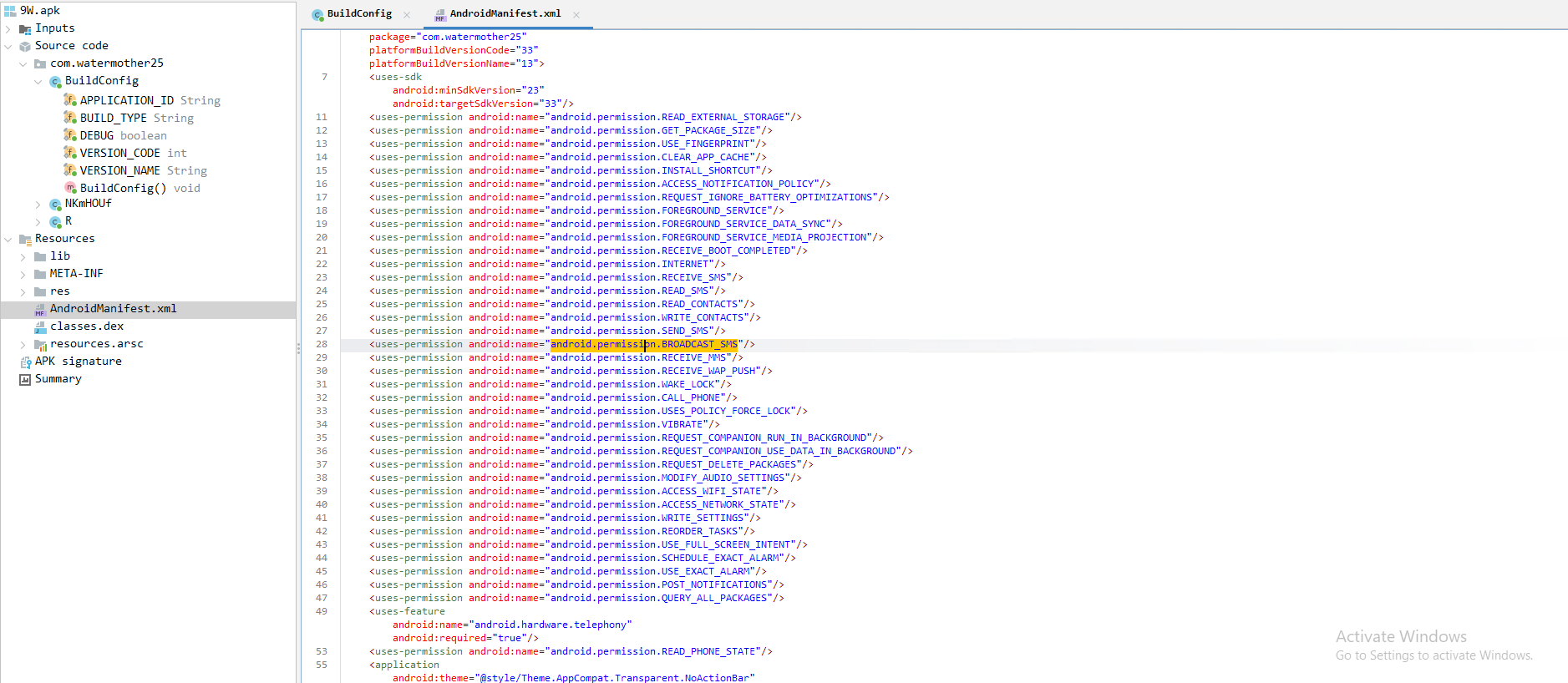

Upon loading the extracted 9W artifact into Jadx, my suspicions were immediately confirmed. The package name matched the one referenced in the dropper: com.watermother25. A review of its manifest exposed the true culprit; this was the core malicious payload the dropper had opened the door for. The permission set was particularly aggressive, clearly outlining the worm-like propagation mechanism I alluded to in the introduction.

At the top of this list is BIND_ACCESSIBILITY_SERVICE. Functioning as the malware’s “brain,” this critical permission grants it nearly total control—allowing it to read screen content, simulate user clicks, and record keystrokes (keylogging). The inclusion of SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW facilitates sophisticated phishing attacks by overlaying fake login screens on top of legitimate banking apps. Furthermore, READ_SMS and RECEIVE_SMS permissions are leveraged to intercept 2FA/OTP codes in real-time, enabling account takeovers. Finally, by combining READ_CONTACTS with SEND_SMS, the malware weaponizes the victim’s own address book to propagate itself to new targets automatically.

Phase 3: Descending into the Native Layer

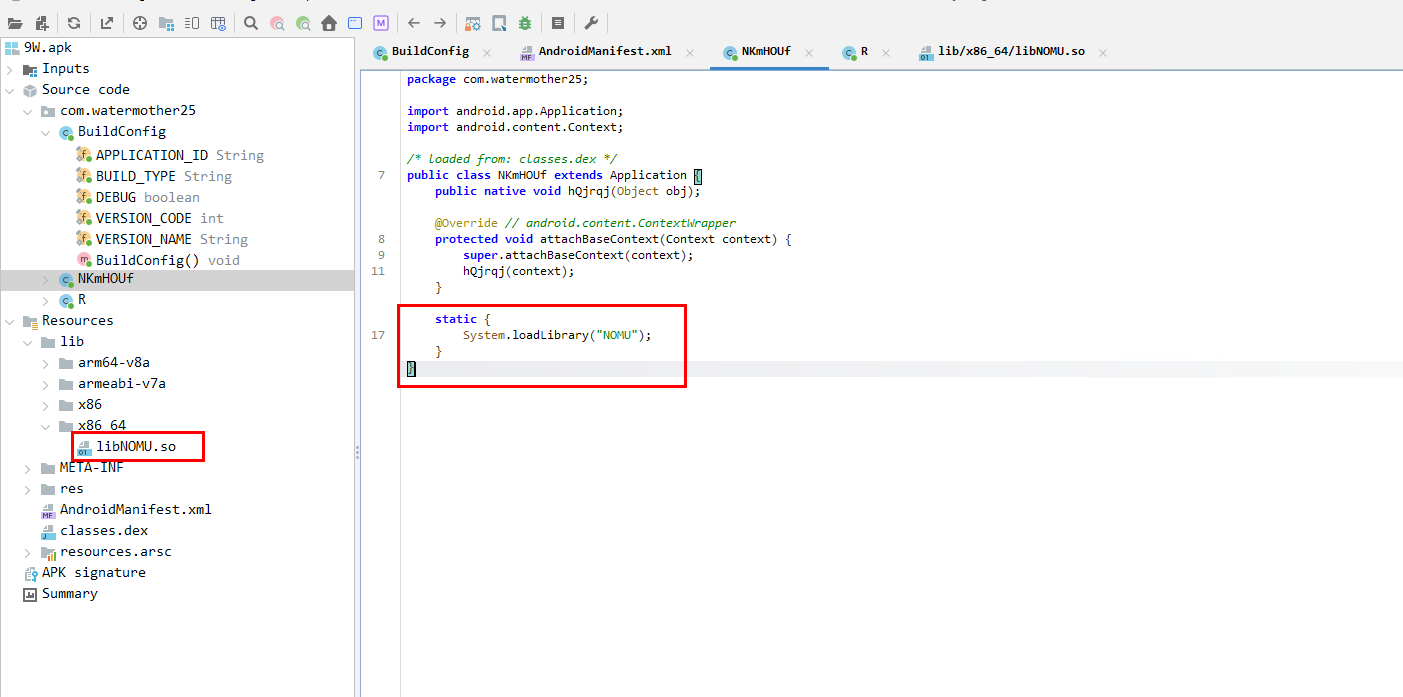

Returning to the MainActivity, I identified a concise but critical code block. The application utilizes the Java Native Interface (JNI) to load a library named NOMU. Its function is explicit: decrypt the emksl file and inject the resulting code directly into the device’s memory. This confirmed that the malware employs Dynamic Code Loading (DCL) to evade static detection. However, this loaded code was not read-only; the NOMU native library was the key to unlocking the encrypted payload.

While shifting logic to the native layer was a decent attempt at evasion, it was not an insurmountable barrier. To analyze libNOMU.so, I transitioned from Jadx to Ghidra. We are now operating at a lower level of abstraction; unlike APK bytecode which runs on the Android Runtime (ART), .so files are compiled C++ binaries executing directly as machine code. This significantly increases the complexity of the analysis.

Upon dissecting the NOMU library, it became clear that while the authors attempted obfuscation, they were stupid enough to leave the decryption key exposed in plain sight within the binary strings. With the key in hand, the only remaining challenge was identifying the algorithm.

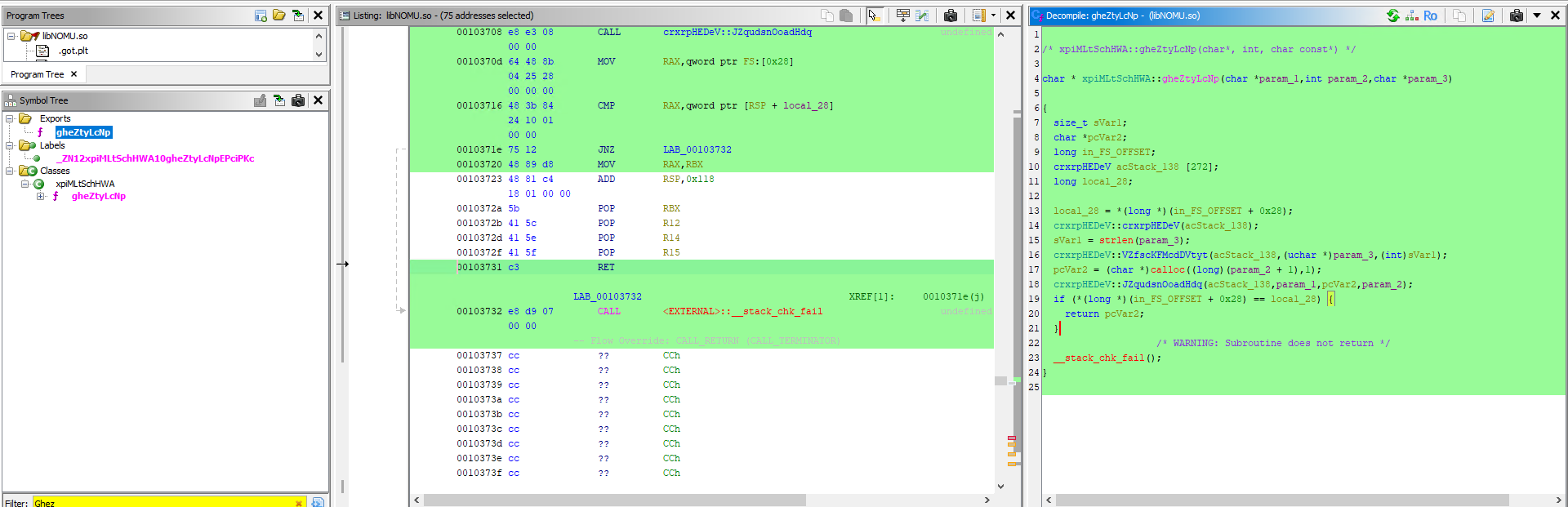

My analysis pointed to a Stream Cipher rather than a Block Cipher (like AES). I deduced this from the memory allocation logic within the native code. The calloc function allocated a buffer using the size (param_2 + 1), where param_2 represented the input size of the encrypted data. Had this been a block cipher, the allocated size would typically require alignment to a block boundary (e.g., 16 bytes) to accommodate padding (PKCS7), resulting in an output buffer larger than the input. However, the 1:1 mapping between input and output sizes, combined with the subsequent byte-by-byte XOR operations visible in the loop, served as definitive technical proof that we were dealing with a Stream Cipher—specifically, a variant of RC4.

Phase 4: Inside the Beast – Analyzing the Decrypted Payload

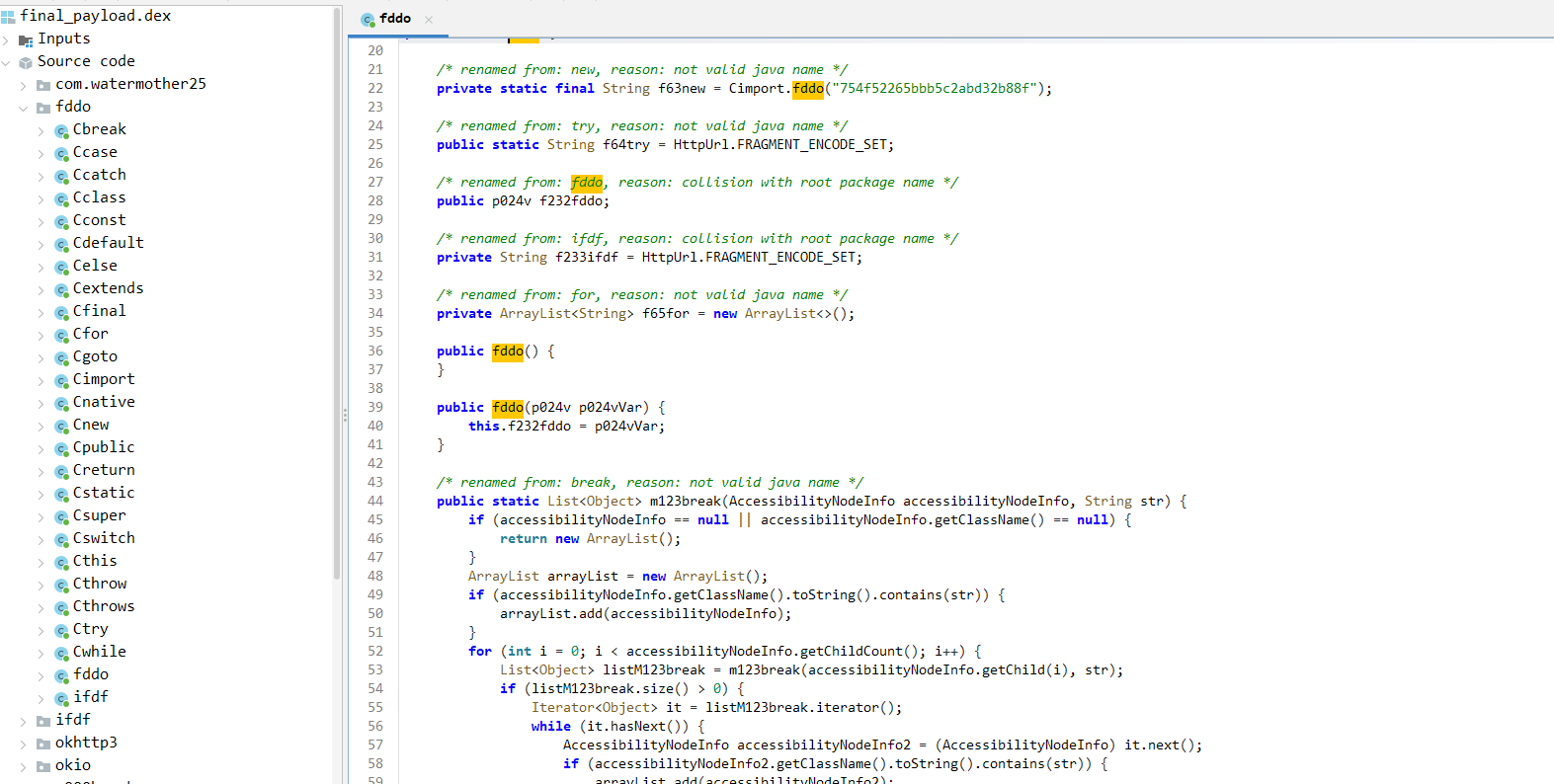

With the final_payload.dex successfully decrypted, I loaded it back into Jadx to finally see the malware in its raw form. However, the authors didn’t make it easy. The code was heavily obfuscated; class names were gibberish like fddo, ifdf, and Cimport, and critical strings were encrypted.

The first hurdle was the string encryption. A recurring pattern emerged where strings were wrapped in a function call like Cimport.fddo("HEX_STRING"). Analyzing the Cimport class revealed a classic RC4 decryption routine hardcoded with the key IeBxF5ygaJ9j2uuMnCx. I wrote a Python script to automate the decryption of these strings, which acted as the Rosetta Stone for the rest of the analysis.

As the strings were revealed, the malware’s full capabilities came into terrifying focus. By analyzing the Cdefault and Cswitch classes, I uncovered how the malware manages its configuration and targets. It uses Android’s SharedPreferences to maintain a local database (likely named main.xml or params.xml) of its state and targets.

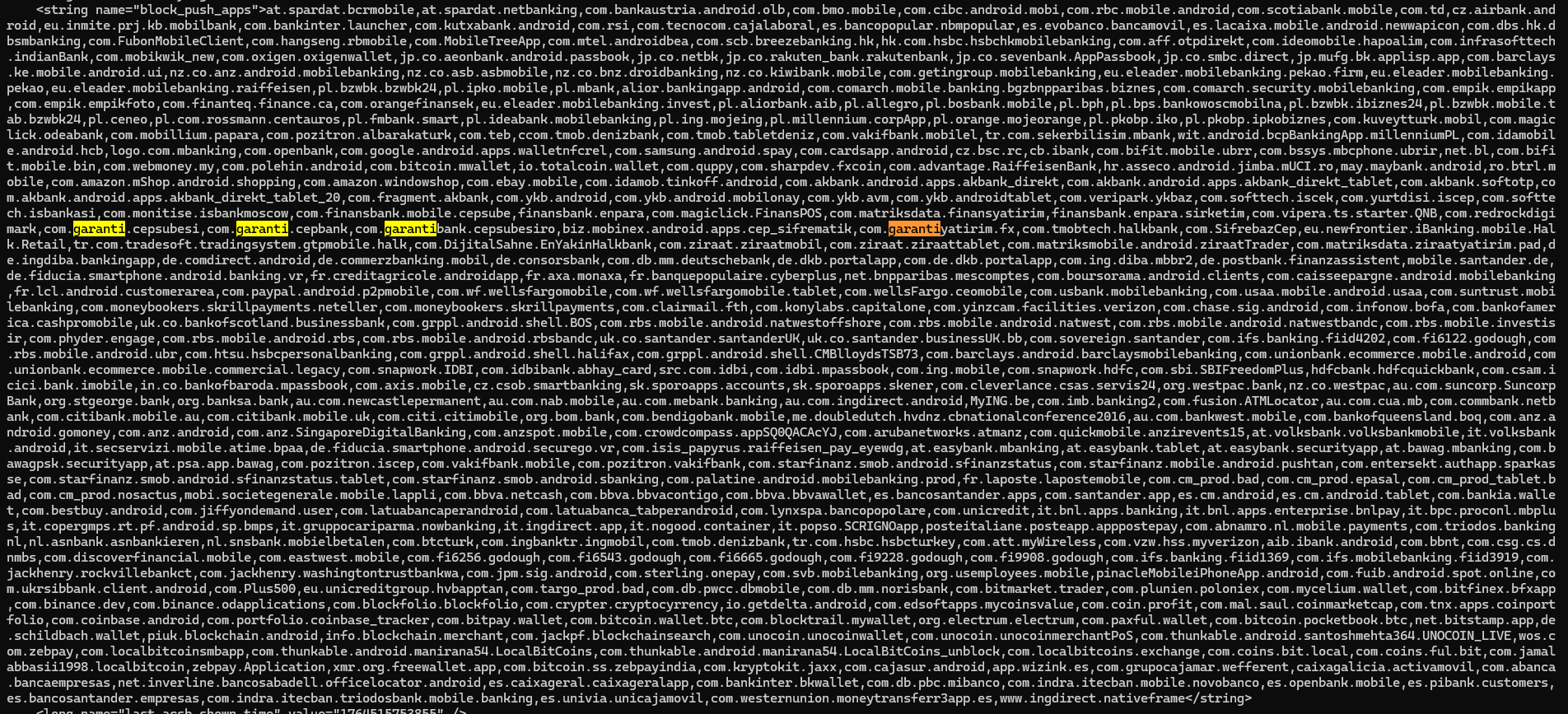

The decoded configuration exposed a massive “Hit List” targeting the Turkish banking sector. The block_push_apps list included major institutions like Garanti BBVA (com.garanti.cepsubesi), Akbank (com.akbank.android), Ziraat (com.ziraat.ziraatmobil), İşCep, and Yapı Kredi. The malware suppresses notifications from these apps to hide OTPs from the victim.

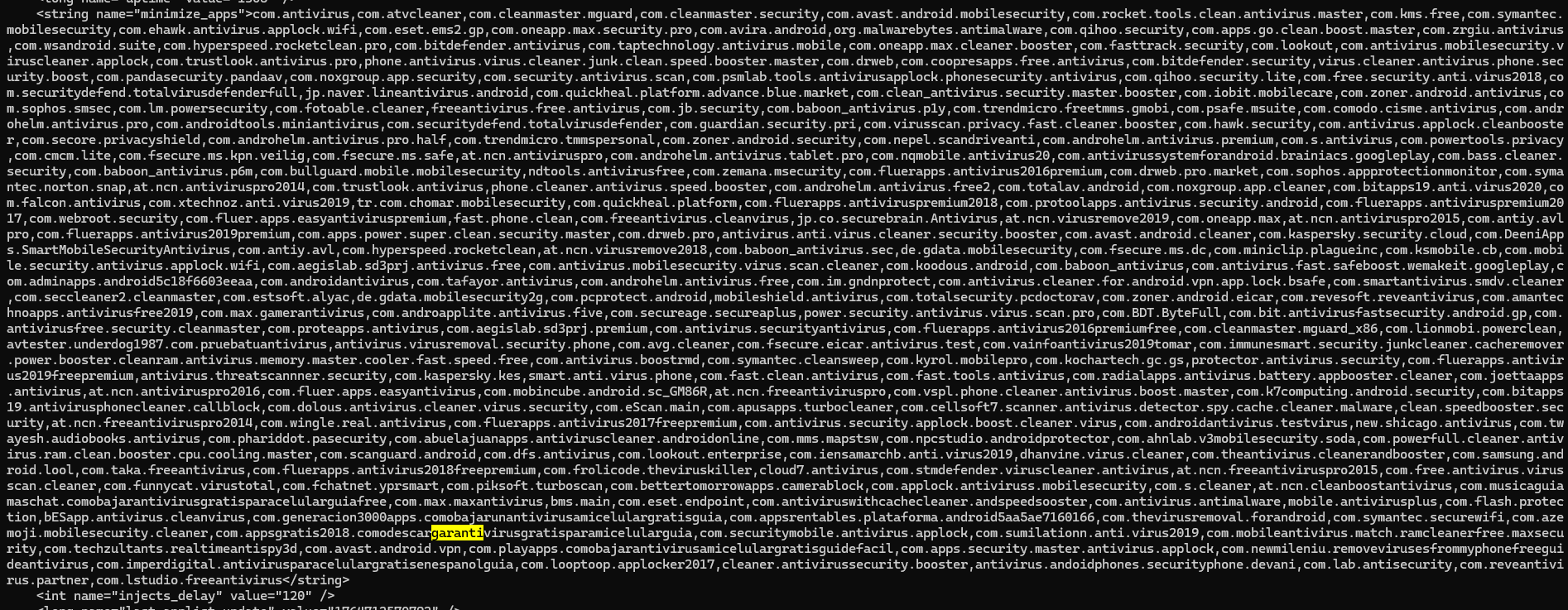

Even more aggressive was the minimize_apps list. This contained over 100 security applications, including Avast, ESET, Kaspersky, and Malwarebytes. The malware’s Accessibility Service actively monitors for these apps; if the user tries to open one, the malware immediately triggers the “Home” action, effectively minimizing the antivirus and preventing the user from running a scan or removing the infection. This wasn’t just a stealer; it was an active combatant on the device.

Phase 5: The Verdict (Conclusion)

The Dropper: We successfully bypassed the initial PackageInstaller trickery and extracted the malformed payload (9W) concealed within the resources.

Native Evasion: Through reverse engineering of the C++ libNOMU.so library, we identified the custom RC4 implementation and extracted the decryption keys that the authors believed were secure within the native layer.

Total Surveillance: By decrypting the configuration and analyzing the fddo package, we confirmed that this malware is a full-fledged RAT (Remote Access Trojan). It boasts VNC capabilities to stream the victim’s screen in real-time, an Accessibility Service to log every keystroke (capturing PINs and passwords), and an Auto-Clicker to self-grant permissions without user interaction.

Financial Theft: The decrypted configuration (main.xml) exposed a targeted hit-list of major Turkish banks. The malware employs Overlay Attacks to harvest credentials and an SMS Interceptor to bypass 2FA/OTP protections, effectively draining victims’ accounts before they even suspect a breach.

Active Defense: Perhaps most disturbingly, the malware actively fights back. It monitors for over 100 security applications and instantly terminates them if the user attempts to run a scan. It also intercepts “Uninstall” dialogs, making removal nearly impossible for the average user.

List of targeted banking applications: https://github.com/ErenCanOzmn/ErenCanOzmn.github.io/blob/main/assets/watermother_banks.txt

List of targeted anti-malware applications: https://github.com/ErenCanOzmn/ErenCanOzmn.github.io/blob/main/assets/watermother_antivirus.txt

See you in the next deep dive. Stay safe.

- Dızmana